A very interesting but little-noticed fact emerged during Canadian pipeline operator and proposed Keystone XL pipeline builder TransCanada’s second quarter earnings call with reporters and analysts on August 2nd, when company CEO Russ Girling relayed that the company had obtained easements from 62% of landowners in Nebraska on the proposed Keystone XL “Mainline Alternative” route:

“…We continue to work collaboratively with landowners in Nebraska to obtain the necessary easements for the approved route. To-date, we have obtained negotiated easements for approximately 62% of the route in the state and we expect that that percentage will continue to rise in the coming months.”

—Russ Girling, CEO of TransCanada (August 2, 2018)

What’s notable is that this percentage is down from the 88% of landowners TransCanada said it has obtained easements with in Nebraska back in 2015.

“TransCanada still hopes to reach voluntary agreements with more than 90 percent of landowners. The percent of easements it has in Nebraska has gone from 84 to 88 since Christmas [2014].”

—Andrew Craig, TransCanada land manager for Keystone projects (January 20, 2015)

What does this mean?

The popular resistance to eminent domain for private gain, and concerns with TransCanada’s proposed foreign tarsands export pipeline have grown even stronger among landowners and communities on the proposed route in Nebraska, since President Obama rejected the KXL project as not in the U.S. national interest in 2015.

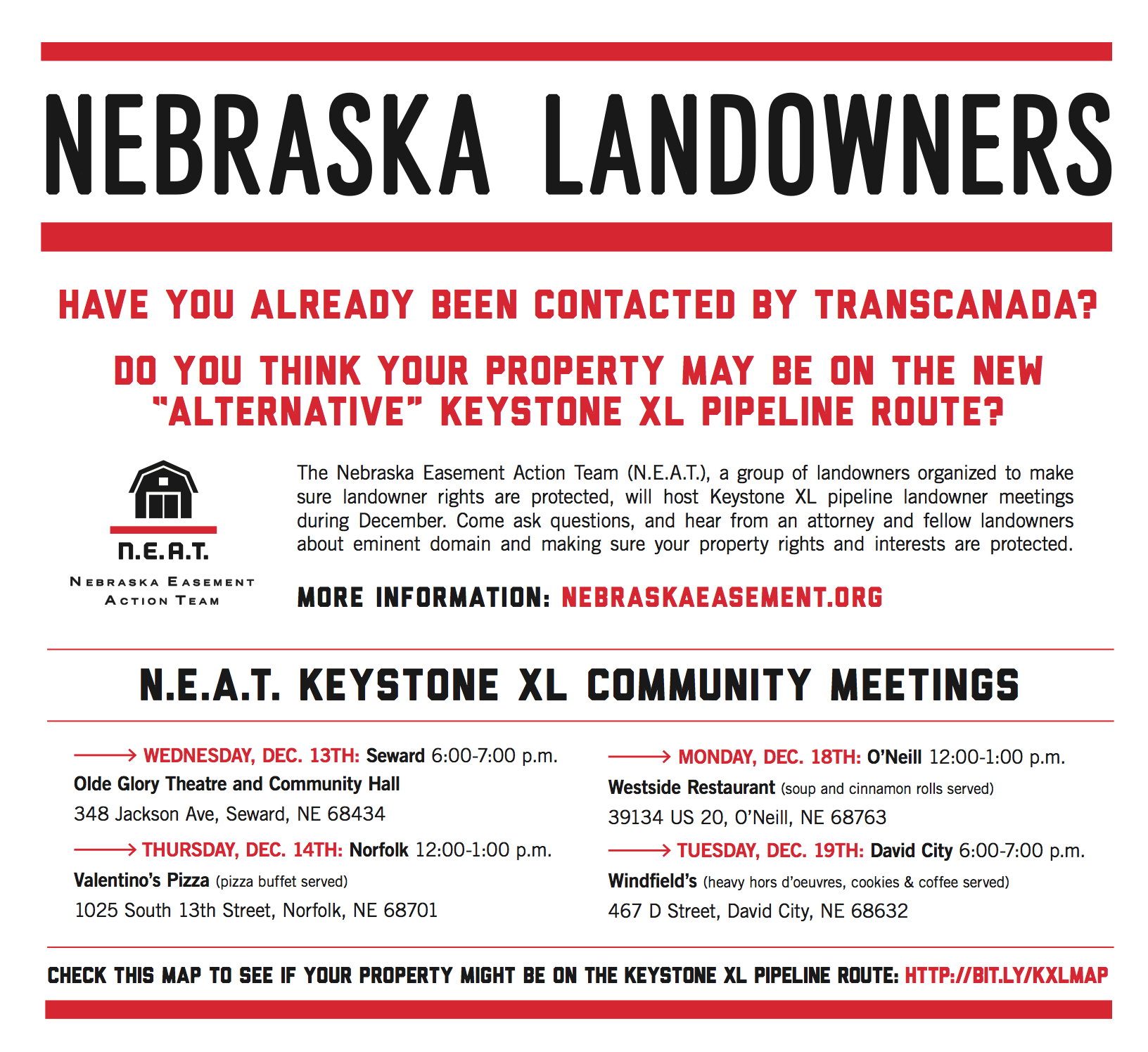

Landowners on the proposed “Mainline Alternative” route approved by the Nebraska Public Service Commission in November 2017 have been receiving regular updates from and attending regular public meetings of the Nebraska Easement Action Team — a landowner-organized collective of families who have refused to sign easements with TransCanada, which has continued to add new supporters all throughout 2018.

By our calculations, more than half of the newly-affected landowners on the Mainline Alternative route have thus far refused to sign easements with TransCanada, despite the company’s extensive and aggressive efforts by land agents to contact landowners and bully them into signing contracts to allow KXL on their land.

These newly-affected landowners who TransCanada must negotiate new easement contracts with for Keystone XL include those who already have the company’s “Keystone 1” pipeline on their land, which was constructed in 2010 — and landowners on a 100-mile stretch of the Mainline Alternative route who had never before been contacted by TransCanada until early 2018.

These landowners had no due process to have their concerns represented, or voices heard in any of the past public hearings on Keystone XL over the years, and many are just now talking with their neighbors and learning about all the dangers and worries associated with a tarsands pipeline potentially crossing their land. The Nebraska Easement Action Team continues to hold regular meetings and correspondence with landowners to update them about the status of pending federal and state lawsuits challenging the permits for Keystone XL.

Landowners’ Case at Nebraska Supreme Court

TransCanada even cited this landowner resistance and reluctance to sign anything with the company in its motion for an expedited hearing by the Nebraska Supreme Court of the landowners’ pending challenge to the KXL route permit in Nebraska. Oral arguments in that case are due to be heard by the Nebraska Supreme Court sometime in October.

Public Service Commission + Election Year

Should the Nebraska Supreme Court side with landowners, TransCanada would be forced to file a new application for a route with the Public Service Commission, a process that typically takes up to eight months. Should the Keystone XL project come back before the Nebraska PSC for another vote, the upcoming elections will come into play as the 3-2 vote to approve the pipeline could be flipped to reject the project, should a candidate opposed to the pipeline be elected in one of two open seats on the Commission that were “yes” votes for KXL in 2017.

Yard sign displayed by NEAT landowners on their properties:

|

|