We are excited to announce that we are once again able to invite a limited number of friends to join us on Saturday, Oct. 16 for this year’s eighth annual harvest of sacred Ponca corn, planted on Ponca Nation land, on Art & Helen Tanderup’s family farm in the path of the now-cancelled Keystone XL pipeline.

Please note re: COVID: We are inviting folks who are *vaccinated* to join the event, and also to wear masks while out in the fields helping harvest the corn. You must register online to attend. (There will also be a film crew documenting the event, and you may be asked to sign a release.)

- WHAT: 8th Annual Harvest of Sacred Ponca Corn in the Path of KXL

- WHEN: Saturday, Oct. 16, 2021

- 12:30 p.m. – 1:30 p.m (Optional): Arrival and socially-distanced brown-bag lunch provided (bring a camping/lawn chair if possible, and your own refillable water bottle)

- 1:30 p.m: Ride the flatbed tractor into the field for circle prayer and harvest the corn (Note: No sandals or open-toed shoes — there are sand burrs and uneven surfaces in the field)

- 3:15 p.m: Return to Art & Helen’s place

- 3:30 p.m – 4:00 p.m: Prayer and closing remarks at the medicine wheel at Tanderups’ Ponca Trail of Tears Pipeline Fighters Arboretum

- WHERE: Ponca Nation land (returned in 2018), the Tanderup Farm near Neligh, NE (address on RSVP)

- RSVP: You must register to attend on the form below

- SHARE/WATCH: Join/share the event on Facebook (Livestreams will be posted here)

In May, a much smaller crowd than usual gathered for the eighth annual planting of sacred Ponca corn. Joining hosts Art and Helen Tanderup and family on the farm for this year’s socially-distanced corn planting were Bold’s Jane Kleeb, Tom Genung from Nebraska Easement Action Team (NEAT), Ponca Tribe of Nebraska Chairman Larry Wright, Jr. and a delegation from the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska’s Language and Culture Committee.

WATCH: 2021 Eighth Annual Sacred Ponca Corn Planting in the Path of Keystone XL (Facebook)

Here’s some more memories from past eight years on the farm for the corn plantings and harvests, and further below is the full story of how the sacred Ponca corn was first restored to the Tribe’s ancestral homeland in Nebraska, after a 137-year absence:

2020 Planting of Sacred Ponca Corn in the Path of Keystone XL

KETV (Omaha): “Keystone XL pipeline opponents plant sacred corn to fight route,” 5/21/17.

“To have a foreign entity come in and take land, it’s something we empathize with,” said Ponca Tribe of Nebraska tribal chairman Larry Wright Jr. “Let our ancestors be. Let’s protect this land… It’s not worth a little boost, for the possible long term side effects.”

Cowboy and Indian Alliance Plants Sacred Ponka Corn in the Path of KXL

(Written by Mary Anne Andrei; originally published June 22, 2014)

That afternoon in November 2013, Sandhill cranes squawked and danced in the distance. Faith Spotted Eagle an elder of the Ihanktonwan Band of the Dakota/Nakota/Lakota Nation of South Dakota, pulled her shawl tighter against the wind and cold, then began to sing. She was gathered with other members of the Cowboy and Indian Alliance in the 160-acre cornfield of Art and Helen Tanderup near Neligh, Nebraska, to bless the land. Afterward, everyone stooped into a tipi, purchased by Bold Nebraska and constructed in Oregon by Nomadic Tipi Makers. The previous day Faith’s grandson Kevin, a shy, young twenty-something, had led a small group of landowners affected by the proposed route of the Keystone XL pipeline in raising the tipi. Inside now, the group huddled around a small fire. They burned sage and prayed to Mother Earth. Then each member shared stories about why they had chosen to fight the pipeline, what it meant to them as individuals and to their families.

Mekasi Camp Horinek—a member of the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma and son of Casey Camp-Horinek, a long-time Native rights activist and environmentalist—admits that when his mother first told him about the Cowboy and Indian Alliance he was skeptical about working with non-natives. “I’ve always been a little bit bitter toward white society,” he said. “I’ve experienced a lot of racism—growing up on the res, living on the res. When I went to town I was always treated differently than others.” But his mother reasoned that the people who live on Ponca ancestral land, like the Tanderups, have developed their own connection to the land. “Their mothers, their fathers, their grandmas and grandpas are buried in the soil the same way that ours are,” explained Horinek. “They have that love and respect for the land the same that we do.”

Convinced by his mother’s words, Horinek and his two youngest sons drove from Ponca City, Oklahoma, to Neligh. Now sitting in a tipi listening to Art explain how his land was crossed by the historic Ponca Trail of Tears on one side and the proposed route of the Keystone XL pipeline on the other, Horinek, whose great grandfather was among those who were forcibly removed to Oklahoma, was deeply moved and began thinking about how best to help the Tanderups protect their land from the pipeline. Planting sacred Ponka red corn came immediately to mind.

* * *

In May 1877, the U.S. Army forcibly removed the Ponca from their land between Ponca Creek and the Niobrara River (approximately between present day Butte and Lynch, Nebraska) to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. The strenuous journey, plagued by extreme weather, claimed the lives of nine Ponca, including Chief Standing Bear’s daughter, Prairie Flower, who was buried in Milford, Nebraska, and White Buffalo Girl, the Daughter of Black Elk and Moon Hawk, who was buried by the people of Neligh, Nebraska. Today, a marble monument marks her grave in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Neligh.

Because they were removed in May, the Ponca had already planted their corn crop and were forced to leave with few corn seeds. When they arrived in Oklahoma at the end of the summer it was too late to plant and the community faced starvation. As a result of these conditions, Chief Standing Bear’s eldest son Bear Shield died in Oklahoma. To fulfill a promise that he made to Bear Shield to bury him in his homeland of Nebraska, Standing Bear traveled north with his son’s body and a group of 65 followers. They were detained in Omaha.

Standing Bear sued the U. S. Army for forcibly removing the Ponca from their homeland—and won. In 1879, he was granted a writ of habeas corpus. The judge ruled that “an Indian is a person” and that the Federal Government had failed to show basis under the law for the arrest and captivity of the Ponca. Standing Bear and many of his followers returned to their home on the Niobrara River and became known as the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska. Those who remained in Oklahoma were registered as the Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma under the Dawes Allotment Act of 1892.

After Horinek returned home from the spiritual camp in Neligh, he immediately contacted his relative, Amos Hinton, the Agricultural Director of the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, who has been working to find and restore the tribe’s five varietals of heirloom corn and establish a seed bank to preserve the seeds for future generations. In 2012, he worked with Nebraska corn geneticist, Tom Hoegemeyer, the Nebraska Department of Agriculture, the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs, and the Intertribal Agricultural Council to plant Ponka grey corn seeds near Kearney with the assistance of the Pawnee Tribe. (The nineteenth-century spelling of the tribe is still used in the official names of the Ponca corn varietals.) The successful planting yielded hundreds of pounds of heirloom seeds. Hinton’s hope is that the Tanderup farm will be maintained as another growing site for the historic corn varietals. “In our creation story the Creator gave us three original gifts: red corn, a dog, and a bow,” explained Hinton. “I am honored to be able to provide my tribe with this historic sacred red corn, which we had not seen since my people were forced to leave Nebraska.”

“I’ve been involved in agriculture my whole life,” said Hinton. He takes great pride in the horses that he owns, in growing his own food, and in subsistence hunting. But he did not make a living in agriculture; for 25 years he worked as a Union pipe fitter and welder in the refineries and chemical plants around Ponca City. He often worked side by side with his younger brother, Harvey. “He was my shadow; we were always together.” In 2011, when Harvey was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer, Hinton rented out his house and moved in with his brother so that he could help take care of him. As he watched Harvey dwindle from 265 pounds to 110 pounds, Hinton struggled with the question, “Why him and not me?” At Harvey’s funeral, he remembers Mekasi Horinek telling him, “I know you feel alone, but you’re not. From here on, I’m your brother.” The two have been close ever since.

Awakened by the reality of his brother’s death, Hinton became alarmed by the rates of cancer and diabetes in his Tribe. He wanted to encourage a return to simple, traditional foods and began working with tribal members to grow their own crops. Hinton soon began a quest to find the lost Ponca corn seeds. Through his initial work with the Pawnee Tribe, he first recovered Ponka blue corn seeds. But it was the sacred red corn that was most important to Hinton. He eventually found a Lakota family in Craig, Nebraska, whose ancestors had harvested the Ponka red corn from the banks of the Niobrara River in the fall of 1877, and had continued to plant and harvest the corn to the present.

Organized by Horinek and Hinton, members of the Cowboy and Indian Alliance came together on the Tanderup farm on Saturday, May 31, to hand plant sacred Ponka red corn seeds. “Our family is honored to have sacred Ponca corn seed planted here on our farm,” explained Tanderup. “The people of Neligh, in 1877, assisted the Ponca by burying White Buffalo Girl. Over one hundred years later, that spirit of humanity continues as we join with our friends and neighbors in replenishing their sacred corn and fighting against Keystone XL.” About thirty members of the Cowboy and Alliance gathered together on a quarter section of the farm as Mekasi Horinek and Amos Hinton led the group in a planting ceremony.

Under the threat of storm clouds, on recently tilled sandy soil, Horinek and Hinton laid out a blue blanket on which they placed a basket of Ponka red corn seeds, a jar with water from the Ogallala Aquifer, a sacred pipe, a sage bundle, and sweetgrass braid. Hinton dug a small hole next to the blanket to burn the sage and sweetgrass. As the group formed a circle around the blanket, Horinek began the ceremony with a prayer to the four directions and later he loaded the sacred pipe with a mixture of tobacco and red willow bark. He then explained to the group the importance of protecting the land and restoring the corn, “Together our families will plant sacred red corn seed in our ancestral soil. As the corn grows it will stand strong for us, to help us protect and keep Mother Earth safe for our children, as we fight this battle against the Keystone XL pipeline.” He then passed around the jar of water from the Ogallala Aquifer and asked each member to drink from it. He also revealed a greater purpose for planting the corn. When Horinek had first conceived of the idea, his hope was that by planting sacred Ponka red corn, the land would become sacred too, and that the Tanderup’s could ask for protection from the pipeline under the Freedom of Religion Act.

After the ceremony, Tanderup climbed aboard his old John Deere tractor to set the 30-inch spacing between the rows. The group of planters lined out behind him and began planting down the rows—some using just their hands while others protecting their backs, used a stick to make the hole for each seed, and then drop, cover and repeat. Even through claps of thunder and occasional hard rain, everyone enthusiastically focused on the planting. After two days, more than sixty volunteers had successfully hand planted 3.5 acres of heirloom corn. Together with the sacred red corn, the Alliance also planted Hopi sweet corn (white), and Ponka grey corn (blue) to symbolize the group’s independence and freedom. They also planted painted-desert corn seeds to symbolize unity.

Despite a devastating hailstorm in early June, the Ponka red corn and the other varietals planted by the Cowboy and Indian Alliance are emerging. Art Tanderup reports, “I can still see the many footprints, handprints, and even some kneeprints from the more than sixty volunteers who took such care in gently placing every kernel at the proper depth and spacing.” Weeding begins in July and harvest is expected in October.

Sacred Ponca “Resistance Corn” Again Planted in Path of Keystone XL Pipeline

by Jane Kleeb

A seed of corn means many things–food, bio-fuel, coating for medicine, bio-plastic, feed for cattle. A seed of corn has also become a cherished symbol of our collective resistance to tarsands and the irresponsible oil production that is risking our land, property rights, climate and water.

For the past three years now, members of the Camp family from the Ponca Nation of Oklahoma have returned to their ancestral homeland in Nebraska to plant rows of sacred Ponca “resistance corn” on Art and Helen Tanderup’s farm in Neligh — this land also lies directly in the path of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline and is sacred ground to the Ponca.

“Once again we made the journey to the Tanderup farm from Oklahoma to Nebraska on the Ponca Trail of Tears to plant the sacred Ponca seeds of resistance,” said Mekasi Camp Horinek, son of Native American activist Casey Camp. “Not only in the soil of our ancestors’ homeland, but also in the hearts and minds of all the people that honor, respect and protect Mother Earth as the roots of these resistance seeds spread across the continents. So does the awareness of fight to stop keystone XL pipeline and protect mother earth for our future generations.”

Mekasi drove through the night to be at Art and Helen’s farm by sunrise. He walked into the field with a strong heart, offered tobacco and sang the corn planting song for a good harvest. This sunrise ceremony is personal for Mekasi and the Ponca Nation. A gift handed down by generations before him continues to live on to this day.

There were no large crowds and no TV cameras. Just two families bonded forever by their shared love of the land and water, respect for the lives of Ponca that were lost at the hands of our government and the resolve to stop Keystone XL.

“We are humbled to plant our second crop of Ponca sacred corn. The partnership with our southern relatives honors those who were forced to leave their homeland, said farmer Art Tanderup. “As we prepared to plant, Mekasi spoke of his young grandfather who walked in treacherous conditions across this farm. The spirit of White Buffalo Girl lives in this community.”

Art and Helen Tanderup’s farm sits both on the historic “Ponca Trail of Tears,” the tragic journey faced by tribal members forcibly removed from Nebraska 138 years ago, and in the path of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline. Helen Tanderup is the backbone of the family farm. She grew up on this land and knows every tree and blade of grass. Helen assisted with the planting and will be out there, as she was last year, tending to the corn. Women may be overlooked in some environmental and energy fights, but with our work to stop the pipeline, women are the heart and the workers who always stand ready to lead.

In addition to the Ponca corn planted in Neligh, the Ponca Nation planted the sacred corn harvest from last year in Oklahoma. In an image of the “four winds,” the Ponca Nation has planted four 20-acre plots using the corn that was harvested from last year’s crop. A powerful action by the Ponca since the corn they planted had not touched their ancestral roots of Nebraska soil for over 130 years.

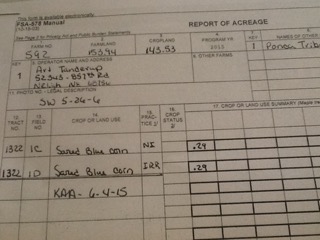

Art Tanderup certified the corn with the USDA to ensure there is a formal record. Our actions have deep personal meaning to our families and now the action of the corn is also documented in our government’s formal record.

Resistance Corn

Casey Camp–a committed Ponca leader, actress and environmentalist–grabs anyone’s attention when she walks in the room. Her strength is felt immediately and her words stay with you long after they are spoken. It is Casey who had the idea to bring the Ponca corn to other families across the globe to share our grit and resolve to stop risky oil and tarsands pipelines.

“The Ponca Corn has continued to be shared throughout the Northern and Southern Americas,” explained Casey Camp. “I have gifted the corn to other Indigenous people’s throughout my travels, and have received words of encouragement, gratitude and prayers for the blessing of the corn. Those who I have gifted in South America refer to it as ‘The Seed of Resistance.’ Tangible in it’s growth and harvest of the fight against Environmental Genocide.”

A Protected and Sacred Place

In addition to the sacred Ponca corn, the Tanderups’ — who refuse to sign with TransCanada for the pipeline and are now in court over eminent domain by a foreign corporation — hosted the September 2014 “Harvest the Hope” #NOKXL benefit, where Willie Nelson and Neil Young headlined a concert on the farm, as well as the world’s largest Crop Art installation, which spanned 80 football fields with the Cowboy Indian Alliance icon and the message “Heartland #NOKXL” and most recently the largest Presidential Seal etched into the land sending Pres. Obama a clear message that his climate legacy is tied to rejecting Keystone XL.

The land which is now protected and farmed by the Tanderup family has deep, sacred roots to the Ponca Nation. Mary Anne Andrei, a gifted writer and photographer, told the story of the White Buffalo Girl, Cheif Standing Bear and the struggle of families that walked before us. Her full story is further below and deserves everyone’s attention. TransCanada may look at this land as another plot on a map they plan to take with eminent domain. We–the pipeline fighters and Sandhills lovers–will protect this sacred ground with everything we have in us.

The resiliency of farmers, ranchers and Native families can not be put into words. Perhaps that is why a seed of resistance corn speaks for us.